This optometrist-on-wheels helps kids see clearly for the first time

In her 27 years of teaching, Becky Yoder has seen many of her students struggling to learn because they did not have glasses.

“There’s usually anywhere between three and five students, out of probably around 20 students, who need or use glasses in the classroom. If children forget their glasses or if they get broken, then I see a lot of headaches and not feeling well,” said Yoder, a third-grade teacher at Galena Elementary School on Maryland’s upper Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake Bay.

Galena, founded in 1763, was named after a type of silver once mined in the waterfront town. It sits a few miles away from the Delaware border in Kent County. In 2017, the population stood at 737, with an 11.6-percent poverty rate, and some people like Dr. Robert Abel Jr. have taken notice.

The American Academy of Ophthalmology estimates half of the world’s population will be nearsighted by 2049.Abel, who is an ophthalmologist in Delaware, echoed Yoder’s concerns, saying the U.S. has “an epidemic of myopia.”

“More and more kids are getting nearsighted from close work and machines, electronic devices,” he said.

While research remains inconclusive about whether or not mobile devices alone contribute to myopia, some scientists suggest their research shows multiple factors, including the use of technology, may be culprits. It is known that so-called “near work” — activities conducted near the eyes like reading, computer games and the use of smart phones — can increase myopia. One meta-analysis found every hour of near work per week increases the chances of nearsightedness by 2 percent.

The American Academy of Ophthalmology estimates half of the world’s population will be nearsighted, or myopic, by 2049, with children being the most at risk.

People with myopia have good vision when looking at an object close up, but poor distance vision. While nearsightedness is easily corrected with glasses, it can lead to other long-term issues for the eye, like cataracts, glaucoma, macular degeneration if left untreated.

Now schools and nonprofits are trying to address what they see as a growing problem, as more children need eyeglasses but can’t afford them.

A 2017 Maryland law requires students get eye screenings in first grade, and again by the time students enter ninth grade. Those years form a huge gap when vision problems could arise — much of the school work children do is performed close to the eyes. This year, state legislators proposed bills that attempted to close that gap, including by giving students at any grade who have behavioral or learning problems free eye exams, but they remain in committee.

In recent years, some states have passed laws to improve vision care for school children. In 2014, an Oregon law went into effect requiring all children age 7 or younger to have free vision screenings, eye exams and glasses, if needed, upon attending public schools. The state recognized the strong connection between vision and classroom performance and seeks to identify and assist those who do not have the visual skills necessary for their grade level. In 2017, Virginia mandated in-school vision screenings to help more schools meet the state’s existing requirements.

Take a 360-degree look inside the Vision To Learn van in the video above.

In Maryland’s Kent County Public Schools, a mobile vision clinic has helped to ensure more children have access to free eye exams, glasses and, as a result, the chance to learn. The national organization works with local funding partners, states and ophthalmologists to offer free eye care to school children in need.

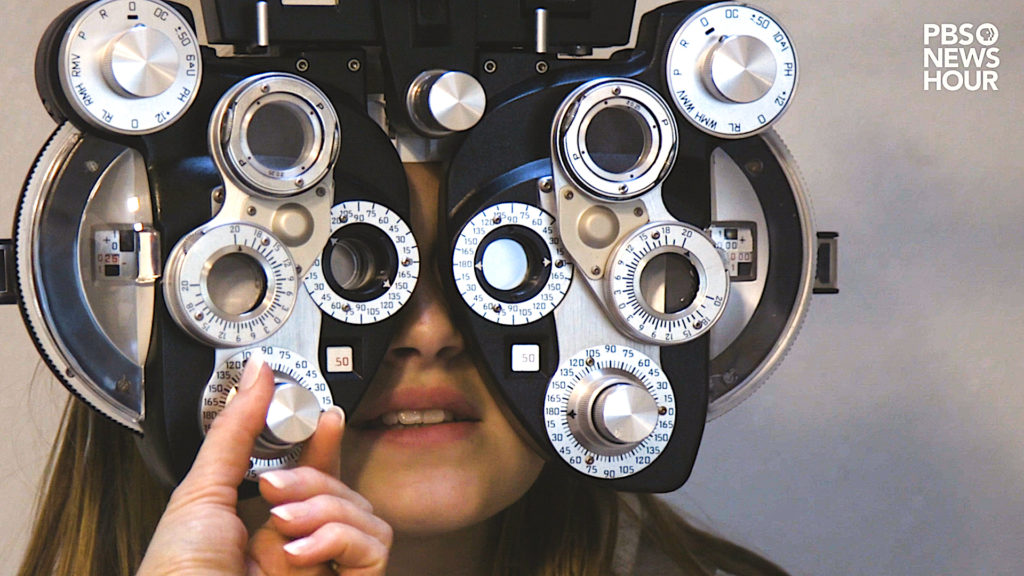

Last November, the nonprofit Vision to Learn made a stop at Galena Elementary. One by one, students boarded a converted 151-square-foot Mercedes-Benz Sprinter van, where an optometrist and optician conducted eye exams inside. Children who needed glasses then selected from a choice of 30 frames.

A few weeks later, the Vision to Learn van returned to hand out the glasses at a school assembly. The glasses were given out like awards. That way, educators and health providers hoped to combat any stigma of wearing glasses.

Vision to Learn has expanded to 14 states, each with their own corresponding mobile clinic van. It’s the brainchild of Austin Beutner, a businessman and philanthropist who recently became the superintendent of the Los Angeles Unified School District. Beutner has said he saw how inner-city students struggled in the classroom and wanted to create a tangible solution — glasses.

Other organizations, like OnSight’s “Vision Van” in New York and VSP Global’s “Eyes of Hope” mobile clinic, headquartered in California, have taken up the same cause in an effort to improve student outcomes.

A number of studies have found students with poor vision have worse academic performance than their peers. Researchers from the University of California at Los Angeles studied Vision to Learn’s program and found a marked improvement on student math and reading scores after they received glasses. Background research conducted by UCLA doctors found that 20 percent of students have vision problems that can be caught by an eye screening and as much as 90 percent of those issues can be fixed with glasses.

Low-income families in this Maryland community often struggle to afford trips to medical appointments, cost of exams and expensive frames and lenses, according to local administrators.

All three of Kent County’s elementary schools and its one middle school qualify to receive federal funding because they enroll a high percentage of low-income students. In 2016, 48 percent of Galena Elementary students received free or reduced lunch.

Lack of transportation can pose an obstacle for students, preventing them from reaching appointments, said Melissa King, a registered nurse for the Kent County Health Department who works with local school health services.

“A lot of our students here aren’t able to get the vision care that they need,” King said. Having doctors come to the students at school eliminates the transportation barrier, she said.

“Vision is critical to education and to everyone.”More than 150 students received eye exams during the van’s four-day visit to the county, according to the Vision to Learn team. In total, they have given away 107,516 free glasses and made 6,079 visits to schools and community organizations in the participating states. For the students who need them, the gesture can be transformational.

“It felt good [getting] some vision [care] I didn’t have in a while,” said 11th grader Tykee Bryant, who had just finished his first eye exam ever and was looking forward to getting his glasses. “Sooner or later, I’ll get glasses, and it’ll help me out.”

Sixth grader Kacie Morris remembered how hard it was to read in class.

“I can see now so I don’t have to like squint or anything,” said Morris after accepting a free pair of glasses from the clinic. “I can actually finally see.”

Vision to Learn plans to continue serving students but is also looking to expand in the near future, Abel said. A practicing ophthalmologist who spearheaded the Delaware chapter of Vision to Learn and now sits on the board, Abel said he is working to double the mobile clinics in his area. He sees the need and possibility to expand outside of the U.S. and hopes to implement similar mobile vision eye care systems for other populations in need, including homeless adults and incarcerated youth.

“Vision is critical to education and to everyone,” Abel said.

ncG1vNJzZmivp6x7sa7SZ6arn1%2Bjsri%2Fx6isq2eYmq6twMdoq6Gho2K8scDOppytqpmowW67zWauoZ2VocButMSlp6xlm56xtHnSnpxmm5yarrO42GadqKpdqbWmecWiqaysXam2rrE%3D